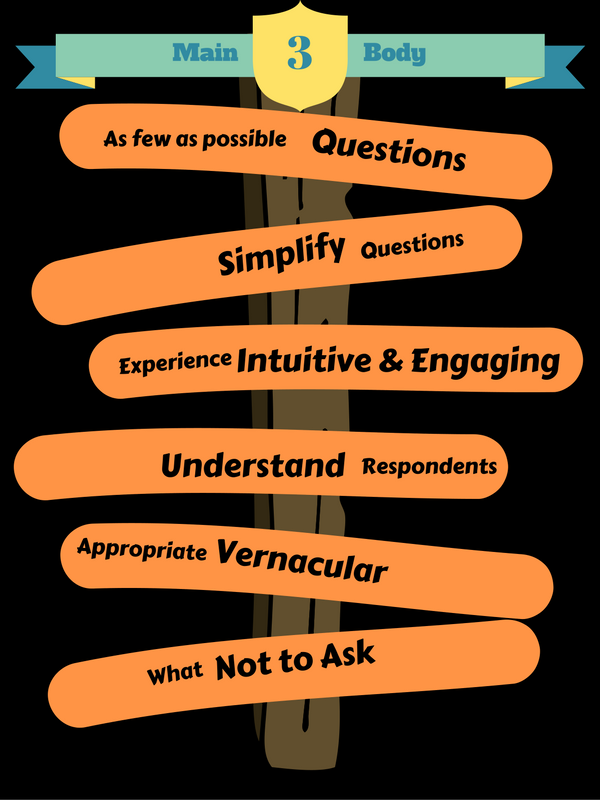

The main body is where 99% of your research questions will be placed. The type of questions you ask and the answers you elicit from those questions largely depend upon the nature of your research.

In this section, we are going to go over a set of six guidelines that you should try to follow as closely as possible. These are guidelines and not rules etched in stone. However, they are important – if not crucial – in the final outcomes of your research. Wherever possible, we will inform you of the cost and benefit of relaxing these guidelines where we see relevance and possibility.

1. Ask as few questions as possible

There was a time if you asked a person to give their feedback, they were delighted to provide it – and in most cases, felt honored that you thought they were important enough to seek their opinions. That, unfortunately, was a long time ago, and surveys should ask as few questions as possible.

Why? Because Survey length has a drastic effect on response rate (a measure of what percent of respondents invited filled out a survey). Across the board, dropout rate increases exponentially as the survey time increases. Therefore, your objective is to keep the survey as short as possible for every respondent.

Keep in mind that this is NOT a suggestion to remove questions that are pertinent to your research. Rather, it is a reminder of the need to get out of the mindset in which we add questions that are on the periphery of our stated goal. One way to avoid this is to use intelligent design and planning, such as branching, skip patterns and auto-code options to reduce the time spent in the survey. If you are using your own panel and already have the respondent’s demographic information, you can either exclude those questions entirely or present it on a page with an option for the respondent to provide corrections, if necessary.

Your goal is to get respondents in and out as quickly as possible. You want to keep that dropout rate to a bare minimum.

2. Simplify questions

It’s a well-known fact that respondent fatigue comes from a long survey. However, a lesser-known fact is the impact of long-worded questions on respondent fatigue. Here is an actual question from a survey. Following it is a simplified rendering that would have done the job better with fewer words.

Original question:

Now we’d like you to think about different words, phrases and quotes that you think can be used to describe the team represented by this mascot. How well does this mascot fit with each of the words below?

Reworded question:

How well does this mascot fit with each of the following?

In this case, if you are unsure of respondent’s ability to recall the mascot from prior screens, you can easily display it on the screen next to the question. A photo is worth a thousand words and in this case it saves you 3 to 5 seconds. However there are exceptions to this rule. In cases where the subject is either too complex or could be perceived to be similar to another concept being evaluated. In those cases it is essential to have long worded sentences to capture the accurate response. An example would be peer to peer surveys in academia.

3. Create an intuitive, engaging user experience

Your perspective is different than that of your respondents. You see questions, while the respondent sees a screen. Make yourself aware of this reality, and keep this front and center in your mind when writing and planning your survey. A high level of emphasis must be placed on creating an inviting screen experience.

This is where a seasoned researcher will object that we are veering off from our stated purpose. So let us give you the reality. We live in a time when most people have 5 to 10 active windows on their monitors, especially if they are at work. Millennials have as many on a 5″ screen. So you are competing for attention in a crowded arena.

An engaged respondent will provide useful information. A disengaged respondent is more likely to start straightlining (link to straightlining article). This is why we offer tools that allow you to preview every screen (desktop or mobile) as soon as you have at least one question on it. Use this feature to create as engaging experience as you possibly can. Do dry runs on your survey and get opinions from co-workers with a slightly different point of view than yours.

4. Understand your respondent base

If you are conducting research for your business, then more than likely, you know your clients and have a good understanding of what resonates with them. If that is not the case, then you need to make an effort to understand your respondent base.

Writing a questionnaire is like having a conversation. If you are not well versed about the person on the other end, it is hard to have a meaningful conversation. A better understanding of respondents goes a long way in creating a questionnaire that respondents will be able to relate to.

For example, there are certain subgroups that are more challenging than others. Gamers, comic fans, sci-fi fans, and employees within the social service industry are some examples. In these cases, if you are not already well versed with unique tastes, we recommend hiring a consultant who specializes in the area. They really are not that expensive when compared to what your sample costs would be. We work with a wide variety of specialists in different research areas and will be glad to provide you with a few recommendations.

5. Use appropriate vernacular

It is a well-known practice to avoid words that are not part of your respondents’ daily vernacular. However, what is commonly ignored is the jargon used amongst subgroups of people. If possible, use the words that your respondents use when communicating about the research subject. However, there are a few special circumstances when this is not a good idea:

• If the vernacular is specific to only one segment of your sample base.

• If the survey is for testing an ad copy and the ad is targeted at a broader group.

6. Do not ask the question you need an answer to

We’re just testing to see if we have your attention!

Put another way, “Do not ask the question you need an answer to directly.” If you are going to remember only one thing from this article, make it this one. Bear with us for a bit, while we make this very important point.

So your 55-year-old aunt bought a new car. Now most aunts, if you ask them how they like their car, will respond with “I love it!” But let’s try a slightly different and more detailed approach. What if you asked questions like: How are the voice controls on your navigation system? You might hear something like, “the darn thing doesn’t know what I am talking about. The other day…..”.

The point is, we have a tendency to defend our choices and we do this so often that we are not even aware of it. We form an opinion and then we go on and ignore any nuance that does not jive with that narrative. You are trying to elicit the facts on your market research survey, and most of the time, a straight question will not get you that.

So how should you pose these questions? Keep them factual and avoid invoking a preconceived notion. Here is an example:

You are trying to determine if a shopper had a good experience at a boutique store. Instead of “How was your shopping experience?” reword it to “How likely are you to recommend this boutique to your friends?” Most people are not going to make a recommendation for a product or service unless they have a certain level of satisfaction. Plus, you just made them think really hard if their friends or a certain friend will like the boutique. Why? Because recommending a place puts their reputation on the line.

How to Write and Test a Market Research Survey, Part 1: Introduction

How to Write and Test a Market Research Survey, Part 2: Writing the Opener/Screener

How to Write and Test a Market Research Survey, Part 4: Writing the Classification Section

How to Write and Test a Market Research Survey, Part 5: Testing the Survey